False Memories and The Misinformation Effect

A false memory is either a distorted recollection of a past event or it is a completely fabricated one. It can range from getting a very small detail wrong to remembering a whole event that never actually happened. The misinformation effect is a study that highlights how easily memories can be implanted into another person by using suggestive questioning. This should be taken into account both when interviewing people and when recollecting our experiences.

What is a false memory and how does it happen?

It is a memory a person has that feels very real and something they can remember in great detail. Sometimes it is an event that happened to someone else, however over the years, they come to believe it happened to them instead. Funnily enough, I have a friend, and through our younger years, my husband always used to tell a story of something that happened when they were together. As the years went by, his friend started telling the story and believe it happened to him instead. It was quite funny the night he started telling the story and my husband turned around and said that didn't happen to you it was me! I am sure you can relate. He didn't deliberately steal this story, it just shows us how powerful the human mind can be.

According to Heathline, a false memory can happen in a few different ways:

Suggestion

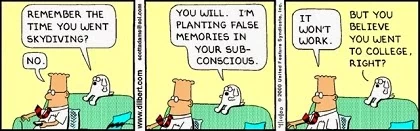

Inference is a powerful force. You may create new false memories with someone else’s prompting or by the questions they ask.

For example, someone may ask you if the bank robber was wearing a red mask. You say yes, then quickly correct yourself to say it was black. In actuality, the robber wasn’t wearing a mask, but the suggestion they were planted a memory that wasn’t real.

Misinformation

You can be fed improper or false information about an event and be convinced that it actually did occur. You can create a new memory or combine real memories with artificial ones.

Inaccurate perception

Your brain is like a computer, storing what you give it. If you give it bad information, it stores bad information. The gaps left by your story may be filled in later with your own created recollections.

Misattribution

In your memory, you may combine elements of different events into a singular one.

When you recall the memory, you’re recalling events that happened. But the timeline is jumbled or confused with the assortment of events that now form a singular memory in your mind.

Emotions

The emotions of a moment may have a significant impact on how and what’s stored as a memory. Recent researchTrusted Source suggests negative emotions lead to more false memories than positive or neutral emotions.

The Misinformation Effect experiment

At her 44th birthday party, psychologist Elizabeth Loftus had a discussion with her uncle about the death of her mother. He told Elizabeth that it was her that had found her mother drowned in a swimming pool. She didn't really remember much about the incident, however over the next few days, all of the memories suddenly came flooding back. She was about to learn however that the memories that came back to her, were actually not real. She later discovered that it was her Aunt that had discovered her mother's body. A simple comment from her Uncle on an event she had little recollection of triggered these false memories. Following on from this she has done extensive studies on the concept of false memories.

Elizabeth is most well known for her experiment called 'The misinformation effect'. This experiment set out to prove that the type of questions a person is asked after an incident could actually influence the way they remember the details of the event. In this experiment, participants were shown footage of a car collision. The subjects were then asked a series of questions similar to the type of questions you would be asked by an emergency services worker after being in an accident. One of the key questions asked was "How fast were the cars going when they hit each other?". Some of the participants were asked this question, while other participants were asked "How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?". A very subtle difference but it is making a suggestion to your brain without you knowing it. From the study, the researchers found that by changing the word hit with the word smash, the participants remembered the footage they had seen differently. They were questioned again a week after being shown the footage. They were asked "Did you see broken glass?". Some of the participants answered 'no', however, most of the people who had been fed the 'smashed' word a week ago seemed to be more inclined to answer 'yes' even though there was no broken glass in the footage they had been shown. The results indicated that the power of suggestion and subtle hints through wording changed the way a person remembered an event.

In 5 experiments and a pilot study, a total of 1,232 undergraduates watched a series of slides depicting a single auto–pedestrian accident. The purpose of these experiments was to investigate how information supplied after an event influences a witness's memory for that event. Ss were exposed to either consistent, misleading, or irrelevant information after the accident event. Results show that misleading information produced less accurate responding on both a yes–no and a 2-alternative forced-choice recognition test. Further, misleading information had a larger impact if introduced just prior to a final test rather than immediately after the initial event. The effects of misleading information cannot be accounted for by a simple demand-characteristics explanation. Overall results suggest that information to which a witness is exposed after an event, whether that information is consistent or misleading, is integrated into the witness's memory of the event.

Loftus, E. F., Miller, D. G., & Burns, H. J. (1978). Semantic integration of verbal information into a visual memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 4(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.4.1.19

When we also look at hypnotic regression which is another tool that people use to recall memories, studies indicate that just the words used in a question asked can cause a person to remember an event differently and that it is even possible to implant a memory of something that didn't happen. The way we ask a question or coach a person to remember an event can influence the way the memory recalled takes shape. The study Construction Rich False Memories of Committing Crime found:

With suggestive memory-retrieval techniques, participants were induced to generate criminal and noncriminal emotional false memories, and we compared these false memories with true memories of emotional events. After three interviews, 70% of participants were classified as having false memories of committing a crime (theft, assault, or assault with a weapon) that led to police contact in early adolescence and volunteered a detailed false account.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0956797614562862#aff-2

False memories and paranormal investigating

Quite often when someone has a paranormal experience, you tell your fellow investigators about it. I mean who better to understand what you have just experienced than a fellow investigator? It is usually not long after the event and you are high on adrenaline and you are excited. You may have not had a chance to sit and think about what has just happened. I know when something happens to me, while I do question things, it isn't until the excitement dies down that I start putting my rational hat on and really think about what has happened and what it could be. In my excitement of telling my colleagues about what is happening, am I slightly embellishing the facts? Was a simple knock now a loud bang? Was a strange feeling suddenly a burst of anxiety? There are many ways that you can subtly embellish a story and not even realize it. As you retell the story more and more, a small detail can change slightly. Much like in a game of Chinese whispers, if you compare your story a few weeks later to what it was originally, is it exactly the same? Our memory also tends to believe these embellishments. We know about false memories and what they can do to our perception of past events. While we may unknowingly begin embellishing our stories, are we also believing these embellishments?

As time goes on, of course, it is possible we will remember things differently. We may even think that something happened to us that didn't happen at all, yet we remember it vividly. Witness testimony can only go so far. A person is not necessarily trying to be deceptive and this is important. They are telling their truth because it was very real to them. Whether or not it actually happened that way, is another story. When we look at the misinformation effect, we have to consider the questions that we are asking when we are interviewing people about their experiences. Our words have a lot of power. They can influence a person. They can educate a person. They can anger a person. They can change a person's mind. How we deliver information can change the way a person remembers an event. It can even influence the way people conduct a paranormal investigation for example. See my article The Observer-expectancy effect.

While there is much debate within the paranormal about what pieces of equipment are not reliable, the most unreliable thing could be us! There is no surefire way to combat this problem, but when it comes to paranormal investigating, take notes of EVERYTHING. The best piece of equipment you can have is a notebook and pen. Note down everything, even as it happens so that your notes are comprehensive and the best they can be. If you have access to one, film everything with a video camera. A video camera is another important tool. It is not necessarily to capture amazing paranormal activity on film, but it is a REAL account of the actual events that have happened as they happened and not a person's recollection of it.

Is there something that you remembered in great detail only to find out it never happened at all or it happened to someone else instead?

References:

https://www.healthline.com/health/false-memory#why-we-have-them

https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-the-misinformation-effect-2795353

Loftus, E. F., Miller, D. G., & Burns, H. J. (1978). Semantic integration of verbal information into a visual memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 4(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.4.1.19

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0956797614562862#aff-2

http://ananael.blogspot.com/2015/03/recovered-memories-are-false-memories.html

If you enjoy LLIFS, consider buying me a book (otherwise known as buy me a coffee but I don't drink coffee and I LOVE books). Your donation helps to fund the LLIFS website so everyone can continue to access great paranormal content and resources for FREE!

Top pages with similar subjects

Don't forget to follow the Facebook page for regular updates

Join the mailing list to receive weekly updates of NEW articles. Never miss an article again!

Buy the latest and past issues Haunted Magazine

Check out the books written by LLIFS